As someone who's built APIs with FastAPI, Django REST Framework, and Flask in different projects, I’ve always wondered how they really stack up when it comes to raw performance. On paper, FastAPI claims to be lightning-fast thanks to async I/O, DRF is often the go-to for full-featured enterprise APIs, and Flask is known for its simplicity and flexibility. But what happens when you actually put them under load in a real-world environment?

This article is my attempt to answer that question, not through synthetic benchmarks or isolated function calls, but by building the same CRUD API with PostgreSQL integration in all three frameworks, deploying them with Docker Compose, and benchmarking them using tools like Locust and a custom httpx script.

Why does this matter? Because API performance affects everything from how many users your system can handle, to how much you pay for hosting, to how responsive your product feels. If you're choosing a backend framework today, or you're just curious like I was, these differences can have a major impact.

I’ll walk through the setup, compare how each framework handles CRUD operations, simulate real-world traffic, and break down the results. My goal is to give you a clear, data-driven perspective on how FastAPI, Flask, and DRF perform.

This book offers an in-depth exploration of Python's magic methods, examining the mechanics and applications that make these features essential to Python's design.

Setup Overview

Before we dive into benchmarks, let me walk you through how everything was set up. I wanted this to be as realistic and repeatable as possible, not a local-only test, and not skewed in favor of any one framework. So I created a level playing field where each API does the exact same job under the same conditions.

Tech Stack

- Frameworks: I built three identical CRUD APIs using FastAPI, Flask, and Django REST Framework. Each one defines an

Itemmodel with basic fields likename,description,price, andin_stock, and exposes the same/items/endpoints. - Database: All APIs connect to a dedicated PostgreSQL container to mimic a real-world production backend.

- Deployment: Everything runs in separate containers managed with Docker Compose, one for each API, one for each of the databases. This made it easy to isolate, restart, and test consistently.

- Benchmarking tools: I used a custom async Python script with

httpxandasyncioto simulate full CRUD operations, and also added Locust to simulate concurrent users. Both tools gave me a nice mix of automated testing and real-time load simulation. - Tested Endpoints: Each framework exposes a

/items/endpoint with support for all four CRUD methods (POST,GET,PUT,DELETE). - Deployment Environment: To avoid any local bottlenecks or throttling, I spun up a small VPS on Hetzner Cloud to run the benchmarks. This kept the results closer to real-world conditions you might face in staging or production.

This setup gave me a good balance between control and realism. If you want to follow along or try your own variations (maybe throw Fastify or Express into the mix), the entire project is containerized and reproducible with a single docker-compose up.

Dockerized Architecture

Spinning up and tearing down three APIs with separate databases can be a huge pain, unless you Docker it. From the start, I wanted this benchmark to be portable, clean, and bulletproof. That meant isolating each framework and its database in its own container, avoiding cross-talk and keeping results honest.

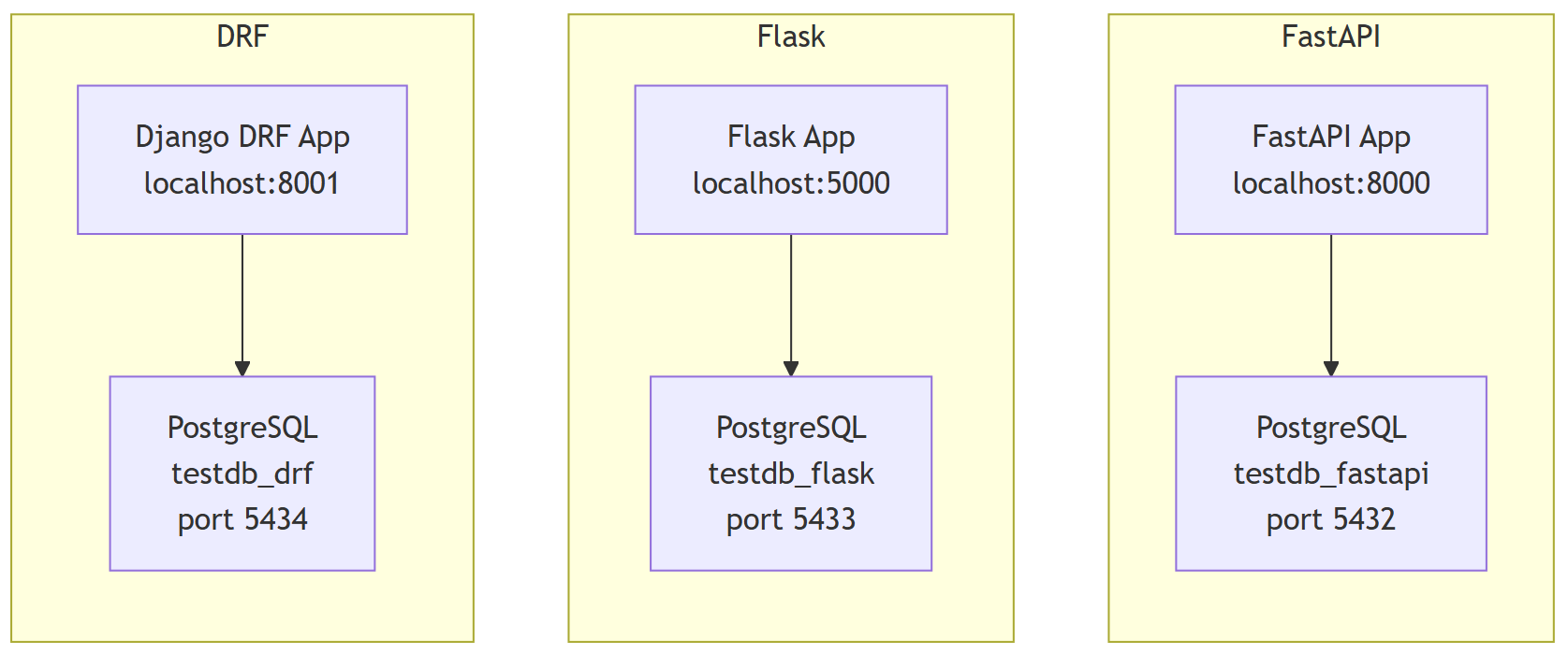

I used Docker Compose to orchestrate everything: three Python APIs (FastAPI, Flask, Django DRF), each backed by its own PostgreSQL database.

Service Layout

Here’s how everything is laid out:

All services are managed through a single docker-compose.yml file, with health checks to ensure each PostgreSQL container is ready before the API boots up.

Exposed Ports

| API | Host URL | Database Container | DB Port | DB Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastAPI | http://localhost:8000 |

postgres-fastapi |

5432 |

testdb_fastapi |

| Flask | http://localhost:5000 |

postgres-flask |

5433 |

testdb_flask |

| Django DRF | http://localhost:8001 |

postgres-drf |

5434 |

testdb_drf |

Each PostgreSQL container is tied to its API via environment variables like DATABASE_URL, so connection logic is clean and centralized. Health checks using pg_isready add resilience, the APIs won’t even try to start until their DB is confirmed healthy.

Docker Compose

For reference, here is the docker-compose.yml file:

services:

postgres-fastapi:

image: postgres:15

container_name: pg-fastapi

restart: always

environment:

POSTGRES_DB: testdb_fastapi

POSTGRES_USER: testuser

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: testpass

ports:

- "5432:5432"

volumes:

- pgdata_fastapi:/var/lib/postgresql/data

healthcheck:

test: ["CMD-SHELL", "pg_isready -U testuser -d testdb_fastapi"]

interval: 10s

timeout: 10s

retries: 10

start_period: 60s

postgres-flask:

image: postgres:15

container_name: pg-flask

restart: always

environment:

POSTGRES_DB: testdb_flask

POSTGRES_USER: testuser

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: testpass

ports:

- "5433:5432"

volumes:

- pgdata_flask:/var/lib/postgresql/data

healthcheck:

test: ["CMD-SHELL", "pg_isready -U testuser -d testdb_flask"]

interval: 10s

timeout: 10s

retries: 10

start_period: 60s

postgres-drf:

image: postgres:15

container_name: pg-drf

restart: always

environment:

POSTGRES_DB: testdb_drf

POSTGRES_USER: testuser

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: testpass

ports:

- "5434:5432"

volumes:

- pgdata_drf:/var/lib/postgresql/data

healthcheck:

test: ["CMD-SHELL", "pg_isready -U testuser -d testdb_drf"]

interval: 10s

timeout: 10s

retries: 10

start_period: 60s

fastapi:

build:

context: ./fastapi_app

container_name: fastapi-app

ports:

- "8000:8000"

depends_on:

postgres-fastapi:

condition: service_healthy

environment:

- DATABASE_URL=postgresql://testuser:testpass@postgres-fastapi/testdb_fastapi

flask:

build:

context: ./flask_app

container_name: flask-app

ports:

- "5000:5000"

depends_on:

postgres-flask:

condition: service_healthy

environment:

- DATABASE_URL=postgresql://testuser:testpass@postgres-flask/testdb_flask

drf:

build:

context: ./drf_app

container_name: drf-app

ports:

- "8001:8000"

depends_on:

postgres-drf:

condition: service_healthy

environment:

- DATABASE_URL=postgresql://testuser:testpass@postgres-drf/testdb_drf

volumes:

pgdata_fastapi:

pgdata_flask:

pgdata_drf:

Docker Compose YAML

The CRUD APIs

All three frameworks expose the same simple resource: Item. It's a small, realistic model with typical e-commerce fields name, description, price, and stock status.

To keep things fair, I stuck to the same table schema and logic in all three implementations. Below, you'll find a quick peek at how each framework handles CRUD. Full implementations are available on GitHub (linked below).

FastAPI

FastAPI shines when it comes to clean, declarative code. I used SQLAlchemy with asyncpg for performance and pydantic for data validation.

models.py:

from sqlalchemy import Column, Integer, String, Float, Boolean

from database import Base

class Item(Base):

__tablename__ = "items"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, index=True)

name = Column(String, index=True)

description = Column(String)

price = Column(Float)

in_stock = Column(Boolean, default=True)

database.py:

import os

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

from sqlalchemy.ext.declarative import declarative_base

from sqlalchemy.orm import sessionmaker

from sqlalchemy.pool import QueuePool

# Use environment variable if available, otherwise fallback to default

SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URL = os.getenv("DATABASE_URL", "postgresql://testuser:testpass@postgres/testdb_fastapi")

# Create engine with optimized connection pool settings for high load

engine = create_engine(

SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URL,

poolclass=QueuePool,

pool_size=20, # Increased from default 5

max_overflow=30, # Increased from default 10

pool_pre_ping=True, # Verify connections before use

pool_recycle=3600, # Recycle connections every hour

pool_timeout=60, # Increased timeout

echo=False # Set to True for SQL debugging

)

SessionLocal = sessionmaker(autocommit=False, autoflush=False, bind=engine)

Base = declarative_base()

main.py:

from fastapi import FastAPI, Depends, HTTPException

from sqlalchemy.orm import Session

import models, database

from pydantic import BaseModel

from typing import List

models.Base.metadata.create_all(bind=database.engine)

app = FastAPI()

def get_db():

db = database.SessionLocal()

try:

yield db

finally:

db.close()

class ItemSchema(BaseModel):

id: int = None

name: str

description: str

price: float

in_stock: bool

class Config:

from_attributes = True

@app.post("/items/", response_model=ItemSchema)

def create_item(item: ItemSchema, db: Session = Depends(get_db)):

try:

# Exclude id from the data since it's auto-generated

item_data = item.dict(exclude={'id'})

db_item = models.Item(**item_data)

db.add(db_item)

db.commit()

db.refresh(db_item)

return db_item

except Exception as e:

db.rollback()

raise HTTPException(status_code=500, detail=f"Database error: {str(e)}")

@app.get("/items/", response_model=List[ItemSchema])

def list_items(db: Session = Depends(get_db)):

return db.query(models.Item).all()

@app.get("/items/{item_id}", response_model=ItemSchema)

def get_item(item_id: int, db: Session = Depends(get_db)):

item = db.query(models.Item).get(item_id)

if not item:

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Item not found")

return item

@app.put("/items/{item_id}", response_model=ItemSchema)

def update_item(item_id: int, item: ItemSchema, db: Session = Depends(get_db)):

db_item = db.query(models.Item).get(item_id)

if not db_item:

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Item not found")

# Update only the fields that should be updated (exclude id)

update_data = item.dict(exclude={'id'})

for key, value in update_data.items():

setattr(db_item, key, value)

db.commit()

db.refresh(db_item)

return db_item

@app.delete("/items/{item_id}")

def delete_item(item_id: int, db: Session = Depends(get_db)):

db_item = db.query(models.Item).get(item_id)

if not db_item:

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Item not found")

db.delete(db_item)

db.commit()

return {"ok": True}

Flask

Flask was set up using SQLAlchemy and classic route decorators. It’s more barebones, but straightforward. I defined the database in a separate database.py file for clarity.

models.py:

from flask_sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemy

from database import db

class Item(db.Model):

__tablename__ = "items"

id = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

name = db.Column(db.String(100))

description = db.Column(db.String(200))

price = db.Column(db.Float)

in_stock = db.Column(db.Boolean, default=True)

database.py:

from flask_sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemy

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

from sqlalchemy.orm import sessionmaker

from sqlalchemy.pool import QueuePool

import os

DATABASE_URL = os.getenv("DATABASE_URL", "postgresql://testuser:testpass@postgres/testdb_flask")

# Create engine with optimized connection pool settings for high load

engine = create_engine(

DATABASE_URL,

poolclass=QueuePool,

pool_size=20, # Increased from default 5

max_overflow=30, # Increased from default 10

pool_pre_ping=True, # Verify connections before use

pool_recycle=3600, # Recycle connections every hour

pool_timeout=60, # Increased timeout

echo=False # Set to True for SQL debugging

)

db = SQLAlchemy()

app.py:

from flask import Flask, request, jsonify, abort

from models import Item

from database import db, DATABASE_URL, engine

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config['SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI'] = DATABASE_URL

app.config['SQLALCHEMY_TRACK_MODIFICATIONS'] = False

app.config['SQLALCHEMY_ENGINE_OPTIONS'] = {

'pool_size': 20,

'max_overflow': 30,

'pool_pre_ping': True,

'pool_recycle': 3600,

'pool_timeout': 60

}

db.init_app(app)

with app.app_context():

db.create_all()

@app.route("/items/", methods=["POST"])

def create_item():

data = request.get_json()

item = Item(**data)

db.session.add(item)

db.session.commit()

return jsonify({"id": item.id, **data})

@app.route("/items/", methods=["GET"])

def list_items():

items = Item.query.all()

return jsonify([{ "id": i.id, "name": i.name, "description": i.description, "price": i.price, "in_stock": i.in_stock } for i in items])

@app.route("/items/<int:item_id>", methods=["GET"])

def get_item(item_id):

item = Item.query.get(item_id)

if not item:

abort(404)

return jsonify({ "id": item.id, "name": item.name, "description": item.description, "price": item.price, "in_stock": item.in_stock })

@app.route("/items/<int:item_id>", methods=["PUT"])

def update_item(item_id):

item = Item.query.get(item_id)

if not item:

abort(404)

data = request.get_json()

for key, value in data.items():

setattr(item, key, value)

db.session.commit()

return jsonify({ "id": item.id, **data })

@app.route("/items/<int:item_id>", methods=["DELETE"])

def delete_item(item_id):

item = Item.query.get(item_id)

if not item:

abort(404)

db.session.delete(item)

db.session.commit()

return jsonify({"ok": True})

Django REST Framework (DRF)

Django REST Framework takes a more structured approach. I used Django’s ModelSerializer and ViewSet, and auto-generated all CRUD endpoints with a router.

models.py:

from django.db import models

class Item(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=100)

description = models.TextField()

price = models.FloatField()

in_stock = models.BooleanField(default=True)

serializers.py:

from rest_framework import serializers

from .models import Item

class ItemSerializer(serializers.ModelSerializer):

class Meta:

model = Item

fields = '__all__'

views.py:

from rest_framework import viewsets, status

from rest_framework.response import Response

from .models import Item

from .serializers import ItemSerializer

class ItemViewSet(viewsets.ModelViewSet):

queryset = Item.objects.all()

serializer_class = ItemSerializer

def update(self, request, *args, **kwargs):

try:

return super().update(request, *args, **kwargs)

except Exception as e:

return Response(

{'error': str(e)},

status=status.HTTP_500_INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR

)

urls.py:

from django.urls import path

from .views import ItemViewSet

# Create explicit URL patterns to avoid router issues

urlpatterns = [

path('items/', ItemViewSet.as_view({'get': 'list', 'post': 'create'}), name='item-list'),

path('items/<int:pk>/', ItemViewSet.as_view({'get': 'retrieve', 'put': 'update', 'delete': 'destroy'}), name='item-detail'),

]

Consistency Across Frameworks

Each API implements full CRUD:

POST /items/– CreateGET /items/– ListGET /items/{id}– RetrievePUT /items/{id}– UpdateDELETE /items/{id}– Delete

Personal note: FastAPI felt snappy and modern. Flask was nostalgic and minimal. DRF? A bit heavy, but rock-solid once configured. Each has its flavour and that’s what made this fun.

Benchmark Methods

To ensure a fair and comprehensive comparison between FastAPI, Flask, and Django REST Framework (DRF), I used two distinct benchmarking approaches: a custom asynchronous script using httpx + asyncio for precise CRUD operation tracking, and Locust for simulating concurrent user traffic in a more real-world scenario.

Custom Async Script (httpx + asyncio)

This method measures the full lifecycle of CRUD operations under concurrent load across all three frameworks.

This article is for paid members only

To continue reading this article, upgrade your account to get full access.

Subscribe NowAlready have an account? Sign In