You know that moment when you're sharing a link to your latest blog post, and the URL looks like https://developer-service.blog/build-your-own-low-cost-cloud-backup-with-hetzner-storage-boxes/?

Yeah, that's not going to fit nicely anywhere.

I faced this problem constantly while managing my blog, sharing free guides, and tracking GitHub repository statistics across different platforms.

Twitter's character limits, newsletter formatting issues, clean QR codes for printed materials, every platform seemed to hate my long, descriptive URLs.

Sure, I could use bit.ly or TinyURL, but then I'd be giving up control over my links, paying for premium features, and most importantly, losing valuable analytics data.

So I did what any self-respecting developer would do: I spent a weekend building my own URL shortener. And you know what? It was way more interesting than I expected.

Full source code link at the end of the article

What Exactly Is a URL Shortener?

At its core, a URL shortener is beautifully simple: it takes a long URL and maps it to a short, memorable code. When someone visits the short URL, they're redirected to the original destination.

Long URL: https://developer-service.blog/build-your-own-low-cost-cloud-backup-with-hetzner-storage-boxes/

↓

Short URL: https://myurl.app/0001ab

↓

Redirect: 302 Found → Original URL

But the devil's in the details. A production-ready URL shortener needs to handle:

- Unique short codes without collisions

- Analytics tracking for every click

- Custom slugs for branded links

- Expiration dates for temporary campaigns

- Security against abuse and malicious URLs

The Technical Challenge: URL Slug Collisions and Uniqueness

This was the most interesting problem to solve. How do you generate short, unique identifiers that won't collide as your database grows?

The Naive Approach (Don't Do This)

My first instinct was to use random strings:

import random

import string

def generate_slug():

return ''.join(random.choices(string.ascii_lowercase + string.digits, k=6))

The problem? With a 6-character alphanumeric string (36^6 = 2.1 billion possibilities), you'd think collisions are rare. But thanks to the quirky birthday paradox, you'll hit your first collision around 55,000 URLs, which is a bit sooner than expected.

The Better Approach: Base62 Encoding with Auto-Increment IDs

Instead, I went with a deterministic approach using database auto-increment IDs:

import string

from typing import Optional

BASE62 = string.digits + string.ascii_lowercase + string.ascii_uppercase

def encode_id(num: int, min_length: int = 6) -> str:

"""

Convert a number to a base62 string, padded to minimum length.

With 6 characters and base62, you can encode up to 56.8 billion URLs.

"""

if num == 0:

return BASE62[0].zfill(min_length)

result = []

while num:

result.append(BASE62[num % 62])

num //= 62

encoded = ''.join(reversed(result))

# Pad with leading zeros to meet minimum length

if len(encoded) < min_length:

encoded = BASE62[0] * (min_length - len(encoded)) + encoded

return encoded

def decode_slug(slug: str) -> Optional[int]:

"""Convert a base62 string back to a number."""

try:

num = 0

for char in slug:

num = num * 62 + BASE62.index(char)

return num

except ValueError:

# Character not in BASE62 alphabet

return None

This approach guarantees:

- Zero collisions: Each ID maps to exactly one slug

- Consistent length: All slugs are 6 characters (e.g., "000001", "000abc")

- Predictable growth: You know exactly how many URLs each slug length supports

- Reversibility: You can decode slugs back to IDs for quick lookup

The math is beautiful:

- 6 characters (default): 56.8 billion possible URLs

- First URL:

000001(ID: 1) - 100th URL:

0001Cv(ID: 100) - Millionth URL:

004C92(ID: 1,000,000)

By padding to 6 characters, all URLs have a consistent, professional look. When you eventually hit 6 characters of actual data, they're already quite short anyway!

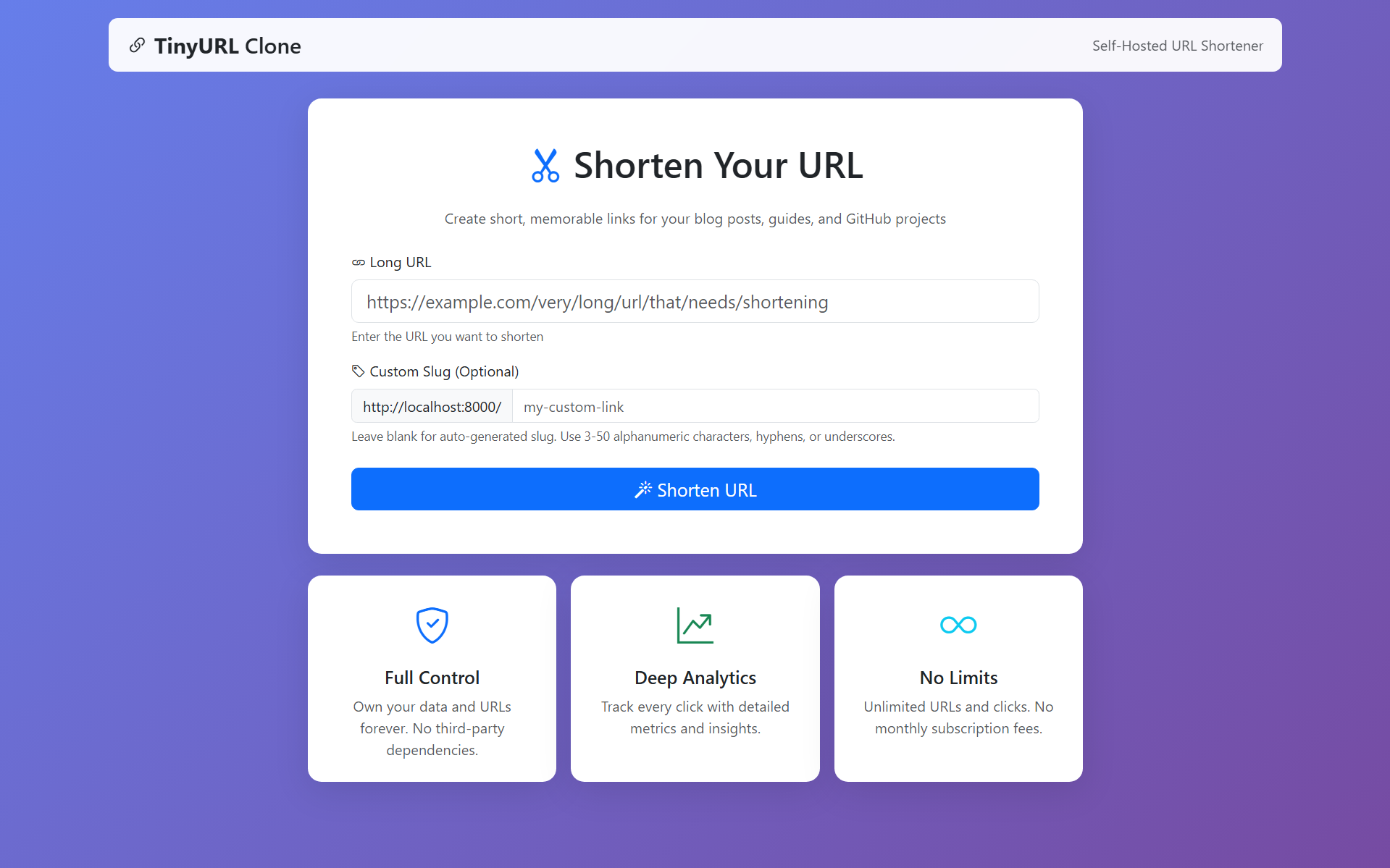

Custom Slugs: The Best of Both Worlds

Of course, sometimes you want a branded slug like myurl.app/blog-launch instead of myurl.app/000x7k. I added support for custom slugs with validation and uniqueness checks:

RESERVED_SLUGS = {"stats", "shorten", "admin", "login", "logout"}

def validate_custom_slug(slug: str) -> bool:

"""Validate custom slug format."""

if not slug or len(slug) < 3 or len(slug) > 50:

return False

allowed_chars = set(string.ascii_letters + string.digits + '-_')

return all(char in allowed_chars for char in slug)

# In the /shorten route:

if custom_slug:

custom_slug = custom_slug.strip().lower() # Normalize to lowercase

# Check if slug is reserved

if custom_slug in RESERVED_SLUGS:

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Slug is reserved")

# Validate format

if not validate_custom_slug(custom_slug):

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Invalid slug format")

# Check if already taken

existing = db.query(URL).filter(URL.slug == custom_slug).first()

if existing:

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Slug already taken")

new_url = URL(slug=custom_slug, long_url=long_url)

else:

# Auto-generate from ID

new_url = URL(long_url=long_url, slug="temp")

db.add(new_url)

db.flush()

new_url.slug = encode_id(new_url.id, min_length=6)

Custom slugs are validated to ensure they only contain alphanumeric characters, hyphens, and underscores (3-50 characters). Reserved slugs like "stats" and "admin" are blocked to avoid conflicts with routes.

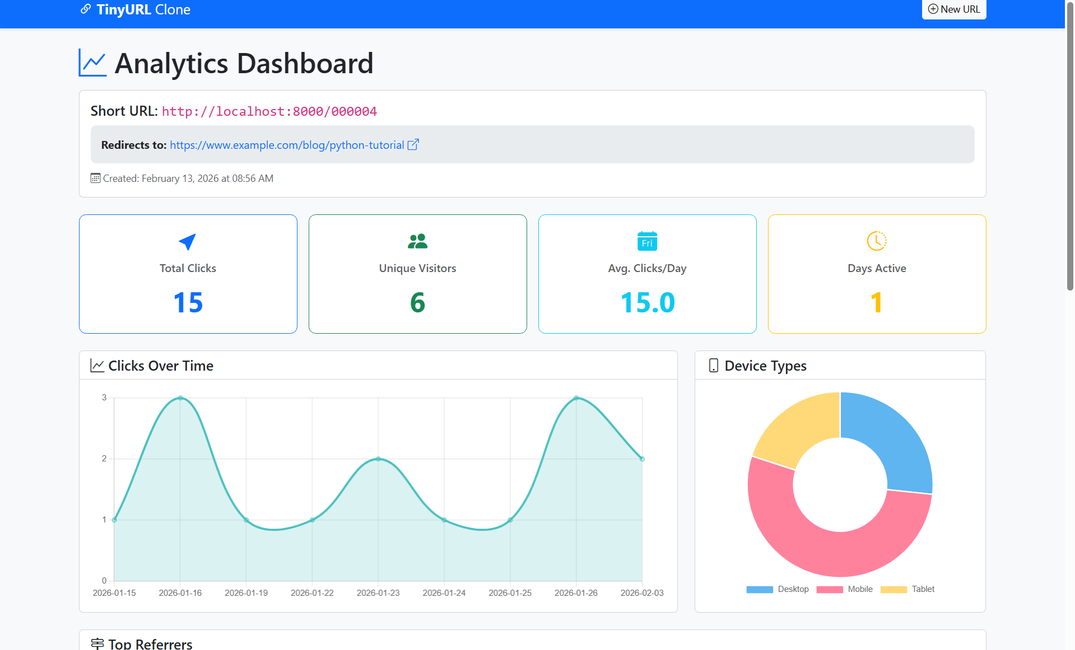

Analytics and Dashboard

This is where building your own URL shortener really shines. Every major platform (Twitter, LinkedIn, newsletters, GitHub README) has different traffic patterns, and I wanted to see them all in one place.

What I Track

For every click, I capture:

class Click(Base):

__tablename__ = "clicks"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, index=True)

url_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey("urls.id"), nullable=False, index=True)

timestamp = Column(DateTime, default=lambda: datetime.now(timezone.utc), index=True)

# Request metadata

referrer = Column(String, nullable=True)

user_agent = Column(String, nullable=True)

ip_address = Column(String, nullable=True)

# Geographic data (would require GeoIP library)

country = Column(String, nullable=True)

city = Column(String, nullable=True)

# Device information (parsed from user agent)

device_type = Column(String, nullable=True) # mobile, desktop, tablet, bot

browser = Column(String, nullable=True)

os = Column(String, nullable=True)

url = relationship("URL", back_populates="clicks")

The Dashboard

I built a simple dashboard using Bootstrap 5 that shows:

- Total clicks with time-series line chart

- Unique visitors tracked by IP address

- Device type breakdown (mobile, desktop, tablet, bot) as a pie chart

- Top referrers with percentage bars (Twitter, LinkedIn, Direct, etc.)

- Average clicks per day since creation

- Recent clicks table showing timestamp, referrer, device, browser, OS, and IP

The most surprising insight? My GitHub repository links get significantly more clicks from mobile devices than desktop. I never would have guessed that people browse code repos on their phones so much!

Note: Geographic distribution (countries/cities) could be added using a GeoIP library like geoip2, but I kept it simple to avoid external dependencies and API limits.

Building it with FastAPI, Bootstrap 5, and Jinja2

Let me walk you through the actual implementation. I chose this stack because:

- FastAPI: Lightning-fast, automatic API docs, async support

- Bootstrap 5: Quick, responsive UI without wrestling with CSS

- Jinja2: Server-side rendering for SEO and simplicity

- SQLite: Zero-config database perfect for side projects

The Database Schema

Simple SQLAlchemy models with a one-to-many relationship:

from sqlalchemy import Column, Integer, String, DateTime, ForeignKey

from sqlalchemy.orm import relationship

from datetime import datetime, timezone

class URL(Base):

__tablename__ = "urls"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, autoincrement=True, index=True)

slug = Column(String, unique=True, index=True, nullable=False)

long_url = Column(String, nullable=False)

created_at = Column(DateTime, default=lambda: datetime.now(timezone.utc))

expires_at = Column(DateTime, nullable=True)

clicks = relationship("Click", back_populates="url", cascade="all, delete-orphan")

class Click(Base):

__tablename__ = "clicks"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, index=True)

url_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey("urls.id"), nullable=False, index=True)

timestamp = Column(DateTime, default=lambda: datetime.now(timezone.utc), index=True)

# Request metadata

referrer = Column(String, nullable=True)

user_agent = Column(String, nullable=True)

ip_address = Column(String, nullable=True)

# Device information (parsed from user agent)

device_type = Column(String, nullable=True)

browser = Column(String, nullable=True)

os = Column(String, nullable=True)

url = relationship("URL", back_populates="clicks")

The URL model stores the shortened links, while Click tracks every redirect for analytics. Using datetime.now(timezone.utc) ensures timezone-aware timestamps. The cascade option means deleting a URL also removes all its clicks.

The FastAPI Application

Here are the key routes (see full implementation on GitHub):

This article is for subscribers only

To continue reading this article, just register your email and we will send you access.

Subscribe NowAlready have an account? Sign In