I once spent several days debugging a Python issue where variables had unexpected values.

My code looked correct, individual functions worked as expected, and tests passed. But when everything ran together, variables took on values I never assigned, and functions behaved differently than I expected.

The issue was that I didn't understand how Python finds variables.

Specifically, I didn't know the LEGB rule, the systematic way Python searches for variable names across different scopes. Once I learned it, scope-related bugs became much easier to identify and fix.

This article will teach you the LEGB rule clearly, directly, with real examples. No jargon. No abstract explanations that leave you more confused.

You'll learn exactly how Python resolves variable names, why your code behaves the way it does, and how to avoid the scope-related bugs that trip up so many developers.

What Is the LEGB Rule?

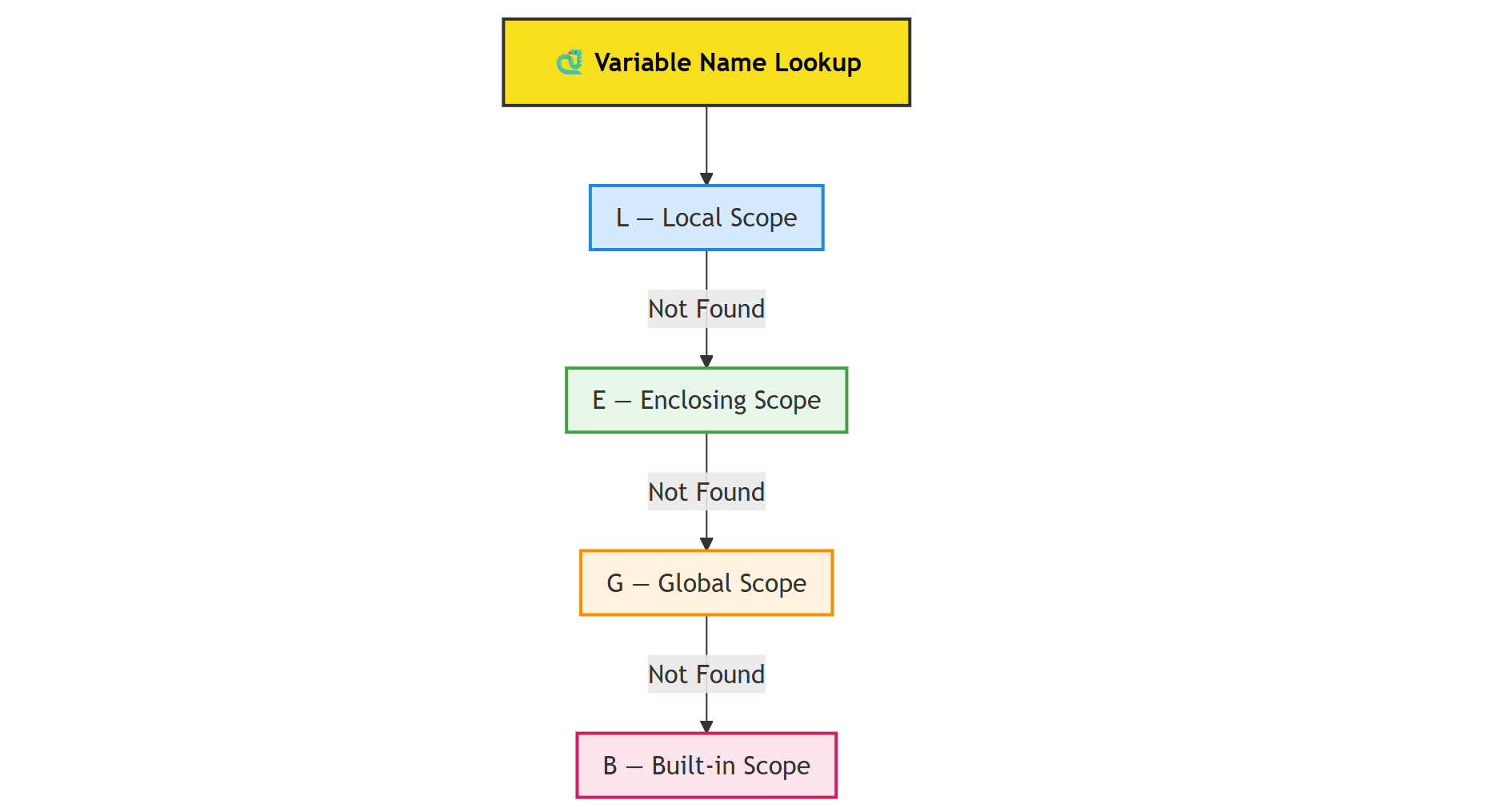

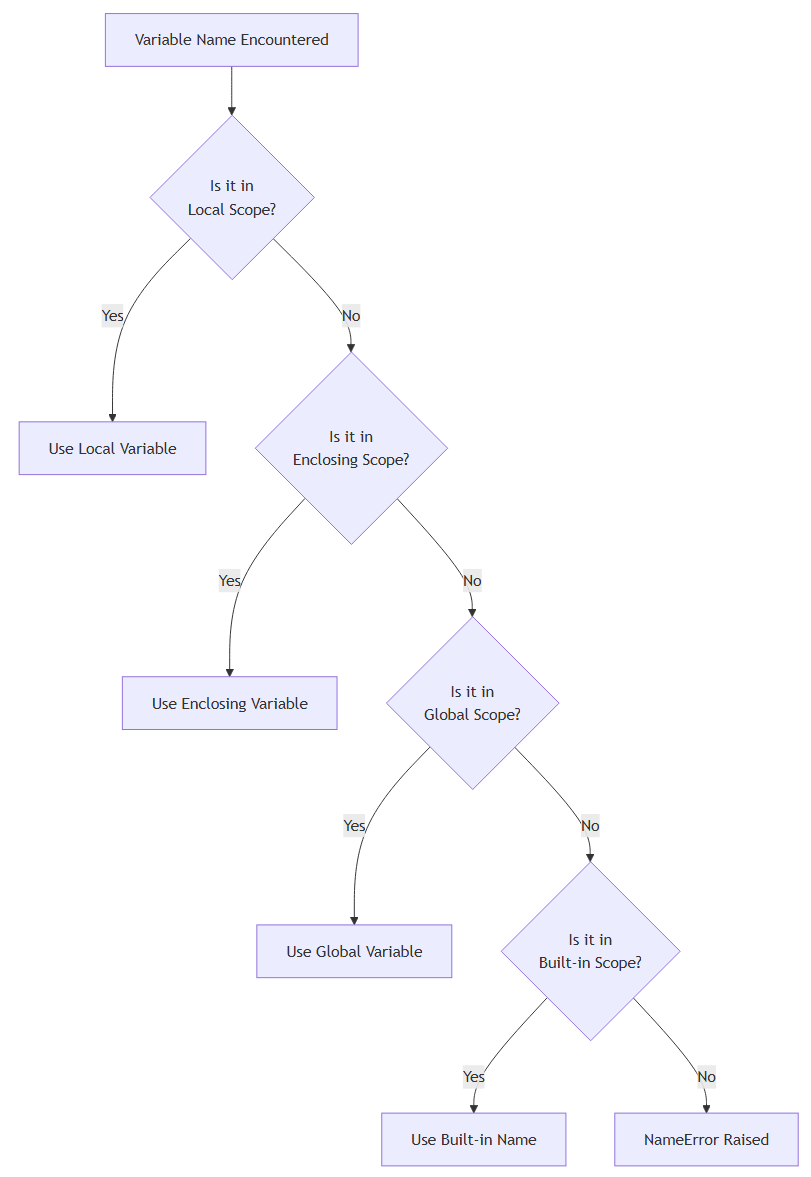

The LEGB rule is Python's search strategy for finding variables. Think of it as a four-step checklist Python follows every time it sees a variable name in your code.

LEGB stands for the four scopes Python checks, in this specific order:

- L – Local: Variables defined inside the current function

- E – Enclosing: Variables from outer functions (in nested functions)

- G – Global: Variables defined at the module level

- B – Built-in: Python's built-in functions and constants

Python searches these scopes from top to bottom, stopping at the first match. If a variable exists in multiple scopes, Python uses the one it finds first in this order, which is why local variables can "hide" global ones.

If Python doesn't find the variable name in any of these four scopes, you get a NameError.

Why the LEGB Rule Matters

You might be thinking: "My code works fine. Why do I need to learn another rule?"

Here's the thing: LEGB isn't optional knowledge. Every time Python executes your code, it's using this rule to resolve every variable name. When you don't understand it, you're flying blind, and that's when bugs creep in.

Knowing the LEGB rule gives you:

- Faster debugging: When a variable has the wrong value, you'll know exactly where Python found it

- Clearer code: You'll write functions with explicit, predictable behaviour

- Fewer mistakes: You'll avoid accidentally shadowing global variables or built-in functions

- Better design choices: You'll know when (and when not) to use

globalandnonlocal

Without understanding LEGB, your Python code works more by accident than by design. With it, you write code that behaves exactly how you intend.

Local Scope (L)

The local scope is the innermost scope. It contains variables defined inside a function.

Example

def greet():

message = "Hello"

print(message)

greet()

Here, message is a local variable. It only exists while the function is running.

Trying to access it outside the function will fail:

print(message) # NameError: name 'message' is not defined

Key Points About Local Scope

- Created when a function is called

- Destroyed when the function returns

- Has the highest priority in the LEGB lookup order

If a variable exists locally, Python will not look elsewhere.

Enclosing Scope (E)

The enclosing scope exists when you have nested functions, meaning a function inside another function.

This scope contains variables from the outer function, but not the global scope.

Example

def outer():

name = "Alice"

def inner():

print(name)

inner()

outer()

Here’s what happens:

inner()looks forname- It doesn’t find it in its local scope

- Python checks the enclosing scope (

outer) nameis found and printed

Global Scope (G)

The global scope contains variables defined at the top level of a module (outside any function).

Example

This article is for subscribers only

To continue reading this article, just register your email and we will send you access.

Subscribe NowAlready have an account? Sign In